Legendary Ontario Climber Dave Lanman Passes

A heartfelt farewell to Dave Lanman, one of Ontario's most talented climbers. Lanman recently passed away from cardiac arrest in his sleep.

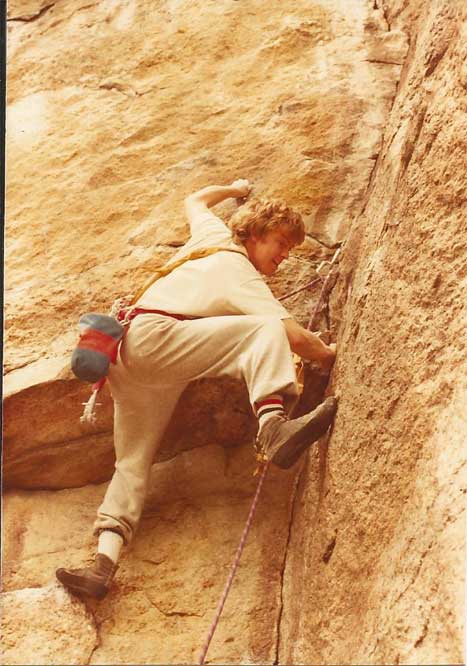

Dave Lanman

(Photo: Reg Smart Collection)

The first time I saw Dave Lanman, he was climbing the strenuous 5.11 overhang of Space Case at Rattlesnake Point with an effortless grace, belayed by George Manson, one of the best rock climbers in the country. The next time I saw him, we introduced each other. He smiled disarmingly and shook my hand, although he was also belaying a struggling leader, winking at a girl and smoking a cigarette, despite having a congenital lung defect and, like me, being too young to buy his own smokes.

We were both teenagers, me from the western suburbs of Etobicoke and Dave, along with his soft-spoken older brother, Steve, Richard Massiah, Steve Labelle and Mike Tschipper came from the eastern suburbs of Don Mills and Scarborough. Most climbers were unrelatably middle-aged, preoccupied with training for the Canadian Rockies and based in the affluent city centre. Dave was a suburban kid like me and was an instant role model for climbing with a few hints for a possible future vector of my own teenage rebellion thrown in.

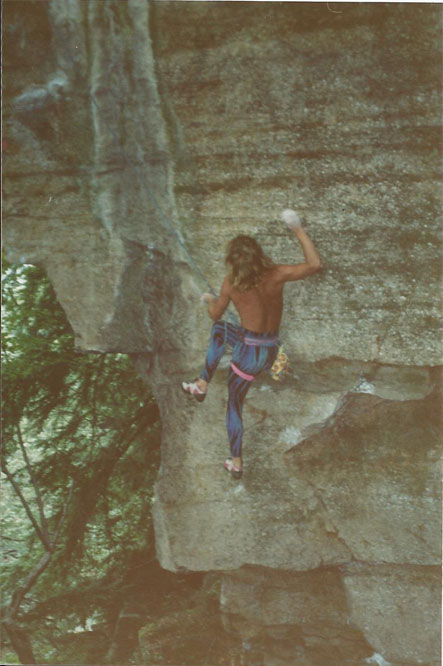

Dave on The Spring 5.9, Gunks, 1982.

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

In the years that followed, we climbed together often on the Niagara Escarpment crags and in Quebec and the Gunks, where his skill and boldness were evident on his ascents of numerous 5.11+, 5.12 and even 5.13 climbs. Back then regardless of the area, they were, of course, protected with nuts, which were often very small and not up to the task of holding falls.

Dave was also the leader of efforts to climb new routes on sight on the unpredictable and steep rock of Bon Echo. It was here that he gained a reputation as a young climber whose routes and climbing were reflections of his own life, make of that what you will. He was perennially broke. On one occasion with my brother Reg, he stepped out of the car in New Hampshire and another climber recognized him immediately and shouted that Dave owed him money. Dave took off down the street, with the other climber in pursuit and was only seen again much later. A much repeated Lanman quote originated when he lowered rapidly from a high point to a belay on the climb that later became known as Fool’s End: “lower me, express!” When George Manson climbed back up to the highpoint, which Dave said was solid, and so George hung often to clean the rock, George found a pack clevis pin hammered into a small hole as the anchor: the cheapest anchor available.

Gourmet dining on the trunk of the car.

From L to R - Richard Massiah, Kevin Lawlor, Mary and Dave Lanman,1986

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

Dave once “borrowed” a boat from the marina to come to the alpine club hut. He racked up from whatever hardware was lying around the hut whether or not it was his own (and returned it later) and sometimes came to the hut for a weekend with no food, and just hung around the kitchen at dinner until someone fed him. Alcohol and marijuana almost always made it into his pack, however, and sharing them added to the sense of high spirits and rebellion.

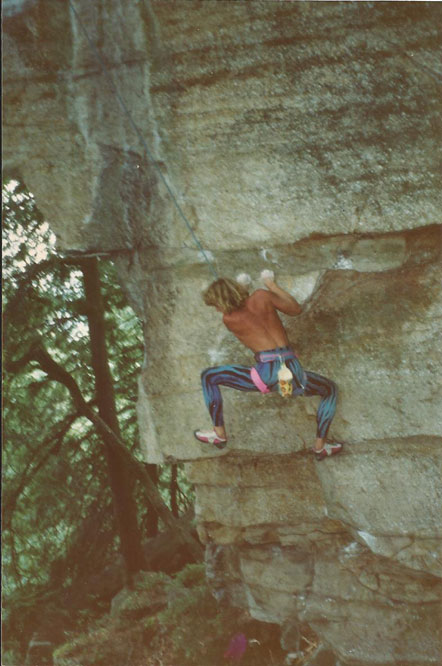

Dave Lanman working a route at a locals-only cliff in the Gunks.

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

Starstruck young climbers, including me, my brother Reg, and talented suburban kids Kevin Lawlor and Adam Gibbs watched as some of the hardest routes in eastern Canada, like Spiderman, a multi-pitch 5.12, emerged from this whirlwind of chaos. Older climbers, responsible for the hut and concerned for the good reputation of climbing were in pursuit of a different kind of atmosphere at Bon Echo, which they described as “something akin to a mountain.” To paraphrase Nietzsche, you have to have chaos in your heart to give birth to a dancing star, but not to climb 5.6. The alpine club newsletter quite reasonably published that “there would be no more shenanigans,” at the hut, and provided a list of infractions no longer to be tolerated. Dave had a T-shirt made that read “Shenanigan Number One,” but the good times at Bon Echo were passing.

Dave Lanman working a route at a locals-only cliff in the Gunks.

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

Dave tried to settle in Montreal and North Conway New Hampshire and eventually put down roots in New Paltz near his beloved Gunks, where he set about on a program of hard new routes. He also did well in early climbing comps, such as the first major event at Snowbird. Although a very bold climber, his attempts to bring the sport climbing ethos to the Gunks were met with hostility and bolt chopping, I sometimes wonder how much he would have achieved if he had stayed on his home Escarpment crags where it was welcomed, but we will never know.

Dave Lanman and Quinton Bennett at a climbing comp in Toronto in the early 90s.

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

A darker note had emerged in Dave’s life in 1980, when his mentor George Manson disappeared with his climbing partners, Sean Lewis, Dave Carroll and Al Chase, on the Cassin Ridge of Denali. Dave began to show a side that was sarcastic, sad and forgetful. The seismic effect of these emerging feelings grew over the years as most of us went on to climb further afield, education; or as work and relationships curbed our climbing, and we got out, temporarily or forever. Dave, however, continued as he had begun, albeit with diminishing returns and longer periods of drinking between hard efforts. Over the years, Dave’s parents had died and his brother Steve died of cardiac arrest in 2014, leaving only a few climbing friends in the Gunks and older friends like Richard Massiah and myself in occasional contact.

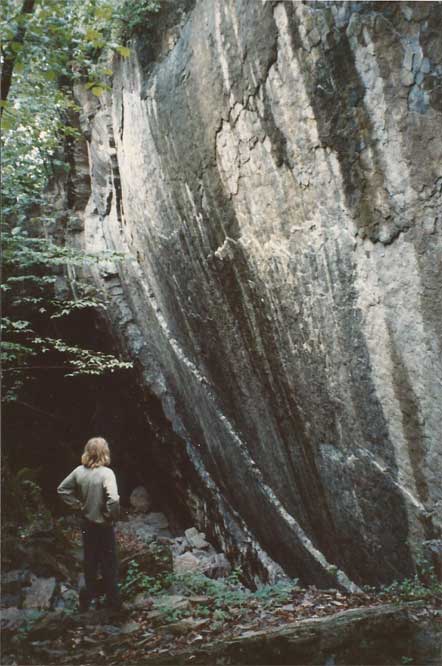

Dave Lanman scoping out his next line.

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

Dave loved my description of our time climbing together in A Youth Wasted Climbing, and occasionally requested new copies for his friends. On January 29, 2017, I sent Dave two more copies. That same day, I was contacted by Gunks climber and mutual friend, Rich Gottlieb. Rich said that after a call from Dave’s landlord, a policeman opened the door of Dave’s apartment and found him deceased. Apart from the fact that Dave had been ill, I have no other information about the cause of my friend’s death.

Dave Lanman at his wedding in the mid-80s.

(Photo: Richard Massiah Collection)

Ours is an era of climbing as a part of a healthy or balanced life, an Olympic sport with scores and workout regimes. I certainly have less nostalgia for the traditional climbing past than some climbers I know who were too young to have been there, some forty years ago. Dave seems a somewhat impossible, decadent figure from that time when there were red wine bottles rather than energy bars in our backpacks, the interiors of tents shimmered with dope smoke and it all at least seemed to mean something more than grades, more even than the climbing itself. Bold, irresponsible Dave was a poet insofar as he set fire to his own life rather than accept any destiny besides the carnal splendour of climbing as he knew it. Others can judge the wisdom and maturity of such a life. I will not.

Thanks, Dave. I was glad to call you my climbing partner and my friend.

Thanks, Dave. I was glad to call you my climbing partner and my friend.